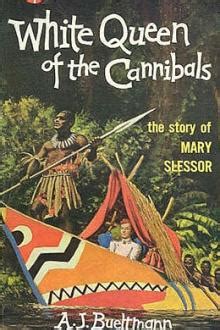

Although I typically try to adhere to the old adage about not judging books by their covers, occasionally I run across a book whose title alone makes it a shoe-in for the Library of Amazonia; White Queen of the Cannibals, by the reverend A.J. Bueltmann, was just such a book. This young adult biography tells the story of Mary Slessor, who lived and worked for decades as a missionary in Nigeria in the late 1800s, and who is most famous perhaps for her work to end the twin infanticide practiced by some indigenous peoples there. The book contains all of the paternalistic racism and “white savior” language that one would expect to find in a book about missionaries written in the early 20th century, making it an educational addition to the Library, while also encouraging me to revisit my own knowledge of and opinions about missionary work in general.

Mary Mitchell Slessor was born in 1848 in Aberdeen, Scotland, the second of seven children that would be born into the working class family. Although her father, Robert Slessor, was a shoemaker by trade, his alcoholism derailed his career and led to his untimely death. As a result, Mary was forced to work as a “half-timer” at a local mill, meaning that she worked half of the day and attended a school run by the company for the other half. Inspired by the African exploits of famous missionary David Livingstone (subject of Stanley’s famous “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?” quote) and probably influenced by her mother, who was a deeply devout Christian, Slessor wanted to be a missionary from a relatively young age. She was willing to make the sacrifices of being a “half-timer” in order to gain an education in furtherance of her goals.

Slessor officially became a missionary at age 28, when she was sent to the Calabar region of Nigeria. The West African country of Nigeria is currently the country’s most populous, and the sixth most populous country in the world. The three largest ethnic groups are the Hausa in the north, the Yoruba in the west, and the Igbo in the east, together comprising over 60% of Nigeria’s population. Prior to first contact with Europeans there had been a long history of highly evolved civilizations in Nigeria, such as the Nok and Oyo Kingdoms and several Islamic caliphates.

Slessor’s intention was to better the daily lives of indigenous Nigerians through the spread of Christianity, and Europeans saw much room for improvement in the region. At the time of Slessor’s arrival in 1876, centuries of the international slave trade had wreaked havoc in many West African states, and many tribes in Nigeria still practiced a form of slavery which, while not as brutal as the chattel slavery to which Africans were forced to endure at the hands of Europeans and Americans, was still terrible from a human rights perspective. Of particular concern to Slessor was the twin infanticide practiced by many tribes in Calabar in conjunction with their religious beliefs, as well as the use of ritual poisoning to determine the guilt or innocence of someone accused of wrongdoing. (Surviving the ordeal meant that you were innocent.)

“The ritual murder of twins at infancy was one of the customs particularly abhorred by the United Presbyterian Missionaries, when they became the first set of European people to live among the Calabar people in 1846. The Efik regarded the birth of twins as a dire calamity; and a woman who gave birth to twins was a subject of dread and horror. The twins were killed by putting them into pots and throwing the pots into the bush. As cursed people, their mothers were either expelled from the town or destroyed with their infants, either by being killed or by being driven from town to the twin-mother’s village. The twin mother was mourned as dead, since the banishment was for life.1

Slessor operated somewhat differently in Calabar than had her predecessors by making more of an effort at adapting herself to the indigenous communities in which she lived. She learned the Efik language, and she ate the local diet as a way to save money. As part of her missionary work, Slessor organized, oversaw, and helped herself to build churches and schools in the regions to which she was assigned. She also inserted herself into all manner of tribal politics and disputes by appointing herself the unofficial adjudicator of conflict. While The White Queen of the Cannibals presents these adjudications as part of the process by which Slessor supposedly eliminated twin infanticide in Calabar, I suspect that she got a certain personal gratification from the assumption of power the lives of other people. As a woman back in Victorian Scotland, Slessor would never have had the chance to be solicitor, judge, and/or jury, or to have such a direct and immediate impact on so many people. Slessor seemed to have an almost pathological need for the juice of first contact, continuously lobbying her missionary organization for permission to go further and further into the bush so that she could always be proselytizing to people who would likely be awed and fascinated by her unusual appearance (ie her white skin), beliefs, and technology. I think that she was likely sincere in her Christian beliefs, but I personally believe she had a personal and psychological motivation, as well.

While Slessor today is feted as the heroic missionary who ended the practice of twin infanticide in Calabar, the truth is that other European missionaries and indigenous Nigerians themselves had been working towards the same goal for at least 30 years prior to Slessor’s arrival. Efik King Eyo Honesty II was particularly influential in eradicating the murders, as he had the influence and authority to actually enforce such major cultural changes. Without his agreement and cooperation, it is unlikely that European missionaries would have been able to effect lasting change on their own.

But should missionaries be forcing their help on people who never asked for it in the first place? This is the question I was left struggling with at the end of Bueltmann’s book. While I’ve been passionate about human rights ever since Peter Gabriel inspired me to start writing for Amnesty International at age 16, and while it’s fundamentally human to abhor the murder of innocents and children. I also know that colonialism has resulted in enormous human rights abuses in the long term. What is right? My gut instinct is to say that Europeans should have kept their noses out of everyone’s business, and yet it doesn’t feel completely right to say that civilizations should have the right to murder infant twins if they decide it’s part of their religion. As incredible as it sounds, given what an extremely opinionated and overly-analytical person I tend to be, I can’t come to a firm opinion about what is right and what is wrong in this situation. I oppose missionary work in general; I cynically see it as essentially Christian concern trolling and colonialism by another name. But this sometimes comes into conflict with my fervent belief in a fundamental standard of human rights, and I’m just glad that I will likely never put myself in the position to have to choose between one or the other.

Original text

Annotated text, web version:

Part 1

Part 2

Annotated text, PDF version:

Part 1

Part 2:

History & Context board

Immersive playlist of Nigerian music

———————————————————————————————————-Notes

1. Robbing Others to Pay Mary Slessor: Unearthing the Authentic Heroes and Heroines of the Abolition of Twin-Killing in Calabar, by David Lishilinimle Imbua